“I knew I never wanted to have a normal job where I worked in an office all of the time,” says Dr. Adam McLain, associate professor of Biology at SUNY Polytechnic Institute.

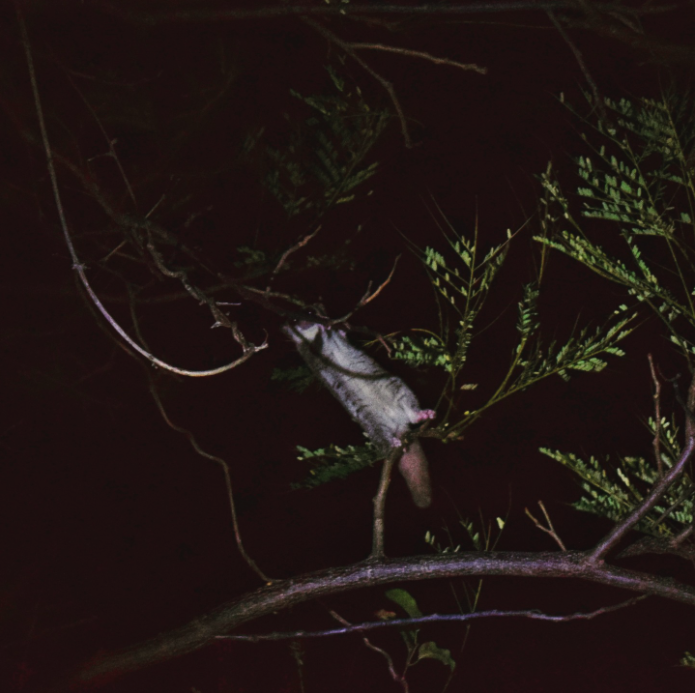

That realization eventually led him to graduate school at Louisiana State University, followed by his postdoctoral fellowship at the Henry Doorly Zoo in Omaha, Nebraska, which included a field program in Madagascar as part of the program. Having done research heavily focused on evolution and speciation in primates, as well as the genetic relationships between different primate groups, McLain had previously worked with lemurs, but through the fellowship, he was part of a group that discovered three new species of dwarf lemur.

McLain was the primary researcher in discovering the Groves’ dwarf lemur in southeast Madagascar, named after the late colleague Colin Groves, a British-Australian biologist and anthropologist, who was working on the project involving this type of dwarf lemur when he passed away.

In 2022, McLain surveyed a cryptic population of dwarf lemurs, located on the island of Nosy Hara, that he said have likely been isolated there since the last glacial maximum (13-14,000 years ago).

McLain and peers collected fecal matter from the lemurs, put it in a suspension buffer to protect the DNA and then extracted the epithelial cells, which McLain will then use to extract the nuclear and mitochondrial DNA from, before sequencing it. He plans on doing that in the near future, as it took several months to secure the CDC permit necessary to get the materials into the country. They are now safely in a secure SUNY Poly freezer.

Genome sequencing during a pandemic

Oxford Nanopore Technologies has a grant stream available to support the sequencing of genomes of various animal species that have none available on record.

During the pandemic, McLain and a research partner at the University of Minnesota decided to apply for some of the funding since it was a project they could do without needing to travel. There were also animals with unsequenced genomes in close proximity at the Utica Zoo.

The first that they sequenced was the Golden Lion Tamarin, a South American monkey that is critically endangered—and the focus of a massive breeding and reintroduction program as a way to increase their population to return it to what it was before their habitats fell victim to deforestation.

McLain contacted the zoo, where he serves on the board of directors, about the possibility of obtaining a DNA sample during the animal’s annual physical, which they did, before being able to sequence the species’ genome.

After publishing their data on the Golden Lion Tamarin, they then looked at what other organisms they might be able to evaluate.

Most recently, they worked on the genome sequencing of Pallas’s Cat, a relative of Fisher cats and other North African wild cats. Once again partnering with the Utica Zoo, who has such a cat, McLain was able to sequence the genome of Pallas’s Cat and recently published related research.

McLain calls the partnership with the Utica Zoo a “win-win.”

“They are definitely interested in raising their profile as a research zoo, and I’m always looking for another fun project to get involved in,” says McLain.

The partnership could possibly continue as McLain and his research partner are currently looking into applying for funding to sequence the genomes of two other species, the Chinese Alligator and the critically endangered Philippine Warty Pig.

In addition to that work, McLain is also researching the impact of DNA methylation and CPG site density in lifelong gene function, or in other words, looking at genes critically needed for life-long function in organisms.

While McLain enjoys being in the field and working with animals, one of his primary motivators is highlighting the much larger issues at hand.

“We’re in the middle of a massive global environmental crisis and a crisis of extinction that’s being fueled in large part by human activity,” notes McLain. “If the work I do can draw attention to these animals in a positive way, maybe somebody somewhere who has money and power will see a picture of a Pallas’s cat or a dwarf lemur and decide that they want to work to help preserve those animals, fund conservation, or create a new national park.”

Reflecting on the phrase, “endless forms most beautiful,” which Charles Darwin made famous, McLain says, “Yes, we have to take care of people. That’s priority number one. But we have to take care of people in a way that allows everything else to flourish, and that’s really what I hope that the work I do draws attention to.”